This is Alpha, a young man who took part in the Mondo Digital Competencies Training with other refugee youths.

He is in Kampala to visit a friend, taking the opportunity to leave the Refugee Settlement where he lives, and agrees to meet me in a local café in Entebbe road, to talk about his experience with Mondo Digital Competencies Training. Our conversation, however, naturally started with a dive into his story, as a refugee, as a young man who escaped one of the most atrocious and long lasting conflicts in our contemporary history. “What makes you share this with me, Alpha?” I asked him. “As refugees, people may not listen to our story”.

Alpha is a 21 years old young man originally from Ruchu, in Kivu province, northern Democratic Republic of the Congo. His first language is Kinyabwisha and Swahili. He also speaks French and English. He learnt Luganda to interact with the local community, but he does not speak it confidently yet.

Despite two of his siblings sadly passing away, Alpha, the fifth born, has a big family, headed by their mother named Bahati Francoise Musabyinana. He has 9 siblings: 5 brothers and 4 sisters.

The conflict

Alpha fled the long lasting conflict in DRC, to reach safety in Uganda with his family in 2014, when he was only 13 years old. Since the beginning of the war, his family moved a lot. First they were dispersed internally, then came back home, but all the sudden they “no longer had stability”. Whilst in DRC, his elder brother was kidnapped but managed to come back home. Their father, a preacher, was targeted and kidnapped by some armed group. That’s when the family decided to escape the country in 2013. Until now, they had no news from him. The instability, the loss and the fear deeply affected his mental health, Alpha recalls.

“I was at school when they attacked. They killed all the teachers. We [the students] ran away. I hid for two days in the forest. I almost took my life - but it was my faith that helped me'' - Alpha reveals - “as if I kill myself I won’t go to heaven”. This is when he found the courage to leave the forest: “I tried to move and found my way back home. Once there, I found no one, only dead bodies. All the houses were abandoned. I was traumatised and scared to be recruited by the armed groups. I have seen children holding guns at only nine years-old. If you take a kid and put them in this kind of environment, they may think it is good''. In fact, Congolese children are the primary victims of war because they are consistently recruited by armed groups(1). As per 2018, UNICEF estimated that thousands of children continued to be used as child soldiers. There is no precise data on the number of children being used as soldiers in the DRC. UNICEF and its partners estimate that, in the Kasaï region alone, between 5,000 and 10,000 children have been associated with the militias(2). As recently as 2021, the UN reports that “Armed groups in South Kivu province of the Democratic Republic of Congo recruited more than 470 children into their ranks”.

What happens to older people, I asked him. “If you are old, they just kill you”. The question of what happens to women specifically, was painfully implicit.

“I was still wearing my school uniform. I knew some friends living in Bunagana, which is 2 to 3 days walk from my home as I thought my family could have been there. I walked.” Alpha remembers.

When he reached the village’s market, he found his mother begging. “She cried when she saw me, as she thought I died too. She said that our father was taken”. That marks the day when the family starts their diaspora in search of safety, and they begin their journey to Uganda, the nearest neighbouring country.

The journey to Uganda

On the very same day they reunited with Alpha, the family walked from Bunagana, a village near the Congolese-Ugandan border, to Kisoro, the first town after managing to cross the border with Uganda. They reached a Pentecostal church where they were welcomed, given some food and some money to take a bus to Kampala.

Alpha recalls that “my mum was not ok, she had been beaten but she tried to look strong for us”.

Despite the sense of safety of leaving DRC, reaching Kampala was quite the opposite of feeling finally protected and stable. “It was tough” - Alpha looks back. “We didn’t know anyone, we didn’t speak the language, we didn’t know the culture”. The family spent 3 days at the old Kampala Police station to try and claim asylum there, whilst begging for food by the road. There, they were even tear-gassed to be chased away, and his little brother was affected. But the family knew they had to stick together to be safe.

It was a man named Sam who went to look for them - they didn’t know him but, as Alpha asserts, he claimed to be instructed by God. He took them to a church called Miracle Centre church Nsambya, a south-eastern suburb of Kampala. Despite he recalls “we were feeling lost” this is where Alpha and his family stayed a few months, offering some labour in return like cleaning and helping, before moving to Kyangwali Refugee Settlement where they registered as refugees.

The Refugee Settlement

Edited photo by Alpha:Kyangwali Refugee settlement

The camp (note that the term "camp" is often used to mean "settlement" by the local inhabitants, whereas the camp itself is the registration centre where asylum seeker go upon arrival) “didn’t feel it was a good place” as Alpha remembers. Though, however small, the plot of land given to the settled refugees was theirs “at least we knew we had somewhere to stay”. However, “as a refugee you never own anything, you can just borrow the land, and you are supposed to build your hut or a tent.” which costs money, that supposedly most people don’t have. Alpha’s elder sister found a job in a restaurant, earning just enough to help the family survive. “At least you are alive - he recalls having thought - many people die. As long as we are alive we don’t want anything more”. Slowly they managed to save enough to pay someone for building a small place for the family to sleep. Alpha admits that religion helped him and many other displaced people “keep going”, accepting that “things are going to be tough”, finding a reason to stay alive, and hoping that one day they will be better, however hard it may be.

“Whoever was in a [refugee] camp, would make it anywhere else.” Alpha asserts.

After 8 years living there, he explains that “life in the camp is hard”. The hardest, he clarifies, is to get food. But he also proudly recognises that he always managed to find something that got him “out” of the struggle to survive, of the anxiety of not making it to the end of the day, of fearing losing hope.

“Education was my way out”.

Alpha looks back to when he was in DRC, before having to flee, he loved school. When he was forced to stop because of the conflict, he promised himself that if he ever had a chance to study again, he would give the best he could.

Yet, like sadly everything else, the life of a refugee student is anything but easy. Alpha explains that he was lucky enough to get a bursary covering 90% of his fees, but even that 10% he had to pay was very high, and a struggle for his family to afford. Also, even if a young refugee manages to get into school, they lack basic resources such as a pen, a notebook and food. Alpha recalls that refugee youth were fed less than the locals.

Despite he found some individuals he could get to trust, what psychologically disrupted Alpha the most was isolation and prejudice from most people in the school. “Teachers cannot understand you, and as our classes were mixed with locals and refugee youth, we faced a lot of discrimination - but that was my only way out of the camp”.

After surviving so much before his school experience in Uganda, Alpha explains, “you expect that if you get a good life, you are equal [to the others], but it is actually worse”.

Nonetheless, Alpha addressed the discomfort head-on, humbly and performing high in school. “As a young student refugee, you have to work twice as hard”, to withstand the jealousy and unfairness. “I don’t know why they have bias when you are a refugee. Even when you reach a job interview it is likely that despite high qualifications, they put you aside, they openly discriminate against you”.

Some time has passed from those days, but still he carries a sense of responsibility for those coming after him. After he graduated, Alpha became a volunteer team leader of mentors at Coburwas, an international NGO supporting refugee children’s education in Uganda, Rwanda, Burundi, and South Sudan. The best part of this role is the interaction with the kids, he shares.

During Covid lockdown, Alpha recalls, everything was very confusing. “Some lessons were even streamed via the radio from the Ministry of Education”. Students in school had to learn online, but none had a computer, he explains. Teachers were not experienced in delivering online, but exams had to take place anyways, so Alpha started on a voluntary basis, supporting other students to prepare, and proudly, succeeding in their exams.

When it comes to his own experience with ICT, “in Uganda this subject is not taken seriously, and focused mostly on the theory”, he observes, however, he recognises “the world is becoming digital, actually it is already. Every school should be doing this more practically”.

The Digital Competencies Training

The great chance to take a real step out of the camp, arrived with World University Service Of Canada, an NGO partnering with local organisations operating within the Refugee Settlement to offer education opportunities to the youth, such as Windle International. Through the Student Refugee Programme WUSC, select 40 single refugee youth of 18 to 25 years of age and with good grades, to obtain a scholarship for a Canadian University and a Visa. This year only 37 of the shortlisted candidates were given the go-ahead to depart towards a new life. Alpha was one of the 3 whose application to University was deferred, but he explains that he will be hopefully prioritised for next year’s cohort.

Windle International Uganda was the local NGO supporting the young refugee cohort offering a pre-departure preparation training. Part of this training involved learning basic Computer Skills to be used to aid integration into a digitalised world such as Canada, but also to feel more confident with tools used at their future universities.

This is when The Mondo Digital Competencies Training (DCT) came in - to support Windle International to train the 40 candidates living in 11 different Refugee Settlements in Uganda, with our 6 modules covering from the basic of computing knowledge to 21st century life skills' topics such as financial literacy, online safety and the different Google tools.

We at Mondo, offered a two-weeks intensive online course based entirely on smartphone use, engaging a mix of distance teaching instruments such as Zoom, Google Classroom, Whatsapp and emails to communicate with the students, ensuring data bundles were provided to tackle the restraints for the students of living in remote areas and having a limited access to the network.

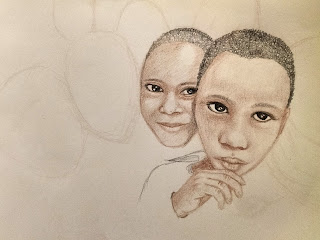

Alpha was one of the committed students of the DCT, trying not to miss any bit of this learning opportunity. “I loved the lessons because they were an everyday reality”. He appreciated having an array of tools that aided his learning experience, for example, the videos on “how to” go about the tools explained. He remarks having learnt many new skills that will be very valuable in his life. For example “learning to write my CV using Canva, searching and finding a job online, is extremely important for my future”. Being able to spot a hack, will help him be protected online. Finally, video and photo editing is helping him record new memories and improve old ones, by re-adjusting and enhancing old hard copies of photos that his mum kept from their past.

“What’s now?” I ask Alpha. He smiles, full of hopes, trying to hold back a sense of disappointment for not being able to set off to Canada this year, after his expectations, naturally were raised.

He knows that his dream will be fulfilled, and his education will continue, studying Medicine at University. He explains that due to the conflict in DRC he saw many people wounded, needing medication. He met amazing doctors at the hospital once, who inspired him to help others, and asked himself: “Why not also me doing this?”

Alpha’s ability to motivate himself is, nonetheless, a great resource that he continues passing on younger generations who experienced the same he did, fueling their ambitions, endurance and hunger for knowledge.

(1) https://www.humanium.org/en/democratic-republic-congo/

(2) https://www.unicef.org/drcongo/en/press-releases/thousands-children-continue-be-used-child-soldiers