“Liar” - I tell myself, when I respond to the little girl walking bare feet at the traffic light, begging for money. “Sorry, I don’t have” with the gesture of my hands. I have - I think - it’s just behind in my rucksack, but I don’t want to open it, and it’s not going to fix her problems. Someone else will probably take the money from her, I don't want her to think people are good and to be trusted because they give money, I allow myself to think. Street children are sadly a normality in such a big city. As a humanitarian worker involved in child protection for years, but mostly as a human being, this may be shocking, especially after seeing the wealth held by a small elite in the very same city, and at the same time a lack of an adequate welfare system, leaving these children at a huge risk of abuse, diseases, malnutrition, discrimination whilst begging on the trafficked and polluted roads. I have discussed this with local friends who, unsurprisingly, all have a story to share that could be part of their personal background, or may know someone who had similar experiences. I researched that there are many international and grassroot NGOs working on this issue (and forming a consortium), but sadly they can’t reach everyone for lack of funding.

By the time I found a justification for not handing out the equivalent of a meal, my boda* hits the gas and we dive into a net of motorbikes giving way at the sound of a honk. The girl’s wide dark eyes are still staring at me, with her little hand spinning half round, a gesture that looks like something in between a “hello” and “give me”.

Few meters away and we pass by one of my favourite junctions overlooking Kampala: Makerere Hill, from where, at the end of a slope you can see the big Gaddafi National Mosque. Regardless of the weather, the air between this point of view and the mosque is always misty: of dust, smog or heated cars. Bodas, matatus**, and cars slalom the slope to get faster to the traffic light, honking their way out of the jam, a strategy needless of any precedence rules on the road. The goldish minaret shimmers above the dusty cloud, reflecting the sunshine. Every time I pass by this spot I hope the traffic would stop me for a few seconds to look at it. I regret not having brought my analog camera but of course, it would not be a good idea to take it out and shoot while moving. We hit the road again, avoiding a clash with another boda by a few centimeters. I tighten up my helmet, the emblem of being a Mzungu*** taking bodas.

In Uganda it is possible to transport essentially anything by boda. Amongst the most bizarre things I’ve seen so far have been: 5 chickens at the back and 2 goats in the front; two pigs at the back; a boda on top of another boda; a wooden wardrobe, a pile of 10 chairs. But today I set a new standard of randomness: a pale lilac, golden handled adult size coffin, tied up at the back of the motorbike. Was it empty or full - I asked myself. Was the man who carried the misfortunate casualty a relative? Was he sad or worried to perhaps cause an accident with a flying coffin? What surprises me in the most subtle way is this balance between, on the one hand, the sense of sacrality and devotion towards religion, the will of God, the world of the spirits and the hereafter, and on the other, the grotesque practical solutions to everyday issues - including death, its prevention, and how to handle it.

The sun is almost setting - very fast, being Uganda near the equatorial line. Beyond the wall beside the road, stands a, for what I can see, girls’ secondary school. A series of yellow school uniforms hang outside the windows of the building, exposing to the heat but also to the dust of the road. Some white t-shirt and underwear are hooked securely with pegs to a hanger, waiting for the last ray of sun to dry them for the following school day. It looks like it’s a boarding school. These, in Uganda, to the eyes of European students may seem like prisons. Wake up call is at 4:00 AM, followed by morning preps - a series of hours spent in the darkness of the class going through homework or preparing for the next lesson. Here, most students hide to sleep, or even masturbate (according to some students’ secret tales) facing hideous punishments. Breakfast is served only after morning preps, around 6.30 AM. The following schedule involves a sequence of lessons only broken by a quick lunch and dinner (rigorously posho**** and beans with no exceptions, all year long) and washing clothes for a total of 2 hours of break before going back to class until night. Students usually sleep 4 hours a night. Students are forbidden from leaving the school apart from holiday, and can receive visits once per term. When I asked the young man who lives with us, what he thinks are the benefits of boarding schools for youths and for the society at last, he replied that there, “you get to become the best of the class”. There is nothing else you need to focus on apart from studying. Your “performance” is at its highest. I wonder if it’s us, the Europeans, the westerners, to be lazy, or this is a whole different system here still embracing a post-Victorian (a legacy of colonial) view of social climbing based on early suffering and little sleep. I wonder how these girls, the owner of the yellow uniforms may feel this evening: are they tired? Are they proud of their achievements? Do they feel comfortable? Do they miss home? The yellow of the fabric moves with the breeze, and reflects what is left of the sunset’s light.

What do these wonderful and peculiar scenes have in common to my eyes? The lack of a camera, the risk of taking my phone out to capture the moment (and very high chance to have it stolen by a passing boda), but mostly the fact that not everything can be seized into a frame, saved into a virtually infinite memory, covered with filters, forgotten for newer instagrammable moments. Why do we feel an untaken photo is like an incomplete drawing? Is the impression of a moment not sufficient to resonate an image into our memory?

|

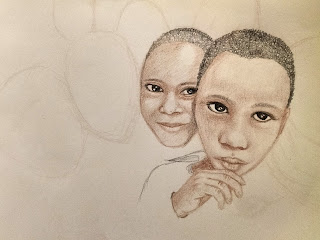

| Unfinished portrait - Ambra Malandrin |

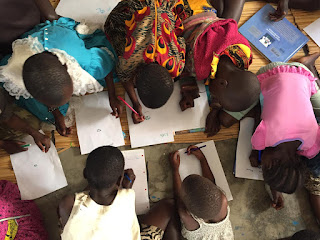

Moreover, photographing people has always been something I don’t feel too comfortable doing. Not only the concept of consent is widely conceived in different ways, and so the informed decision for which the subject chooses to be in the photo. But also because, I ask myself how I feel when strangers take photos of me out of curiosity, or perhaps beauty within their frame. I find it key to observe very deeply if the approach with which we take pictures at people is the same as that we engage when photographing a rare flower, a curious monkey, or a leaf on a tree, a landscape. People’s photography should always have at its very core the story of the subject. And this story should be speaking about dignity, reality, joy, pain, too, but never frame the subject as a passive consequence of the environment where they find themselves in. At least, this is one of the thoughts I matured to face my eagerness to snapshot everything that makes my eyes vibe.

Besides, when it’s not the human element I want to photograph, there are so many rules to take good photos that sometimes, I fear to miss the chance to just enjoy the moment. It would be too disappointing not to capture the beauty before my very own perception.

The little girl’s eyes, the mosque at the end of the slope, the bodas carrying literally anything you can think of, the yellow uniforms hanging from the window. These are some of the photographs that will rest impressed in my visual memory, but not that of my camera. A pair of eyes can, sometimes, take the best photos.

Glossary:

*Boda boda, also called boda: means of local transport by [private motorbike’s riders. Very dangerous but fast.

**Matatus: private minibus, other means of local transport. They usually have 16 seats but they can carry up to 20 people.

***Mzungu: is a Bantu word that means "wanderer" originally pertaining to spirits. The term is currently used in to refer to white people.

****Posho: is a type of stiff maize flour porridge made in Africa.

.jpeg)

.jpeg)

.jpeg)

.jpeg)

.jpeg)

.jpeg)

.jpeg)

.jpeg)